Thirty-Year-Old ‘Snail Mail’ Leads to Collection of Extinct Species Discovered by Texas A&M-Galveston Professor

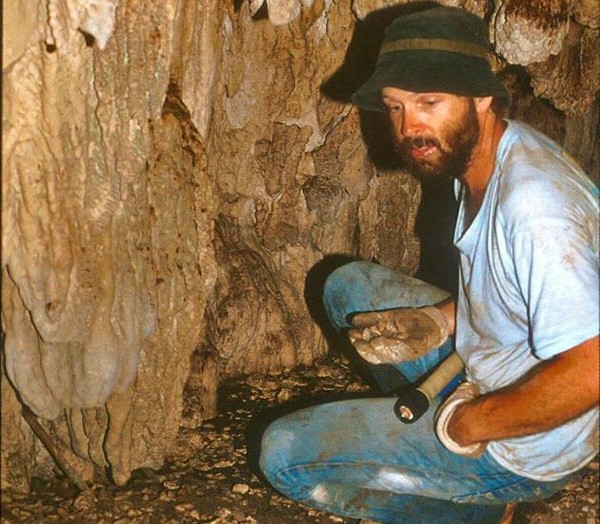

Dr. Tom Iliffe collects snail specimens from inside a cave during a trip to the South Pacific in 1987.

Dr. Tom Iliffe collects snail specimens from inside a cave during a trip to the South Pacific in 1987. When Dr. Tom Iliffe checked his email a few weeks ago, he never expected to read a message about a collection of 30-year-old snails.

This message came to Iliffe, a professor in the Department of Marine Biology at Texas A&M University at Galveston, from Collection Manager John Slapcinsky of the Florida Museum of Natural History. Slapcinsky was inquiring about a collection of Pacific Island snail samples Iliffe had collected over thirty years ago in the South Pacific.

After the unfortunate passing of a colleague at the museum, Slapcinsky was helping to clean out the vacant office and happened upon a collection of hundreds of lots of snail samples gathered by Iliffe decades prior. He was floored, even giddy.

A snail expert himself, Slapcinsky told Iliffe his collection could include several new species and perhaps the last-known records of now-extinct snails.

“Many Pacific Island land snails are endangered, and if you’re considering extinctions in recent times, half are mollusks, and most are land snails” Slapcinsky explained. “So we’re working with a consortium of different museums to gather information about collections of Pacific Island land snails because they’re such an endangered group.”

Slapcinsky is hard at work cataloging the specimens Iliffe discovered, but he needed help georeferencing the samples and their respective origins, thus the email.

“I immediately wrote back to John, sending him a copy of my collection notebook from the trip listing the names, location (latitude and longitude), elevation, distance from the coastline, and ecological description of each collecting site. I’m incredibly excited to see where we can go from here with these specimens and the otherwise-irretrievable database they represent,” Iliffe said.

The project was moving forward. Then, the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Funnily enough, Slapcinsky said social distancing couldn’t have come at a more ideal time for him. The scientist was thankful for the time to focus on this specific project.

“This is the perfect thing to be identifying and studying while stuck working remotely,” Slapcinsky said of the so-far 700 samples representing anywhere from 5,000 – 7,000 individual shells he’s been busy identifying and cataloging.

The details and descriptions in Iliffe’s notebook are helping Slapcinsky to better source the specimen and shell samples to study existing scientific literature to see if the snails are described somewhere.

“There’s a lot of work involved, doing this. I’m looking through all the literature ever written about this area and this species to see if they have been described. There’s a lot of documenting, detailing and measuring shells,” Slapcinsky said.

Journey to the South Pacific

In 1987, Iliffe organized a year-long cave exploration expedition across 12 locations in the South Pacific. Iliffe specializes in the evolution and conservation of the biodiverse species inhabiting marine caves, as well as technical diving within the context of extensive cave systems.

He secured funding from the United States National Science Foundation (NSF) to explore and research underwater caves in Tahiti, the Cook Islands, Tonga, Fiji, Western Samoa, Niue, New Zealand, Southern Australia, Tasmania, New Caledonia, Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands. Iliffe spent roughly one month at each location and collected a substantial number of snail specimens that he detailed in his above-mentioned collection notebook.

During his explorations, Iliffe was in touch with officials at the museum and they encouraged him to collect whatever samples of the understudied animals he could find.

“Sometimes snails fall into cave entrances or shell deposits build up over time. Often, and even at that time, they’re locally extinct or fully extinct, so you would only find deposits in caves,” he said. “I kept a bag in my pocket, would go collect, preserve them appropriately, then be sure to detail everything I could. There was no GPS at that time, so I had topographical maps of the areas where I was. I plotted the areas as accurately as possible and included details about the collection site.”

Iliffe said he was thrilled to be involved in the project, but that part of it was bittersweet.

“These may be some of the last or only collections of these animals ever made,” he said. “I’ve worked with National Geographic on several conservation projects, one of which is a repository of genetic information for animals. We’re trying to leave behind a firm record of what was there. It’s honestly just sad. The problem today is that species are disappearing before we know they even exist, which is likely in this case,” he said.

‘Snailing It’ In Differing Environments

Iliffe isn’t the only one concerned with snail conservation at Texas A&M – Galveston. Coastal Ecology Ph.D student Janelle Goeke studies marsh periwinkle snails along Texas’ Gulf Coast.

Specifically, Goeke researches how the periwinkles are responding to flora and fauna-based changes in their salt marsh environments. Like Iliffe and Slapcinsky, Goeke knows how it can be the smallest creatures that have the largest or significant impacts on their respective environments.

“They’re incredibly important in shaping salt marshes, as in high enough densities, they can actually consume all the plants in an area of marsh, eating it right to the ground and leaving the marsh bare,” explained Goeke. “Here in Texas, the marsh periwinkles are one of the most important food sources for blue crabs, and are also consumed by some species of wading birds.”

Though there are notable differences between land snails and the marine snails Goeke researches, she notes the various survival adaptations that protect them from predation and help them evolve to changing environments are both fascinating as well as a large dividing factor.

“Marine snails are capable of surviving underwater for long periods of time, and require a very wet environment, like a salt marsh, to survive. This is because they have gills in order to breathe, unlike land snails, which have lungs. Marine snails also differ from land snails in that they have an adaptation called an operculum, a structure that they can seal over the opening to their shell when they retreat into it. This helps prevent them from drying out, and can help to protect them from predation,” she said.

More animals than people realize fall into this group, Goeke said, making studying them even more crucial in the face of those with endangered statuses.

“Many land snails still live in very damp environments, like leaf litter in forests, or buried in the soil. Some species of snails have even evolved to live in the desert, although they have a lot of specialized adaptations that allow them to survive without drying out. Snails are an incredibly diverse group that includes animals many people might not even recognize as snails, like limpets, cowries and nudibranchs,” she explained.

Crawling Forward

Slapcinsky echoes Iliffe’s and Goeke’s concerns about endangerment and extinction. He explained that many causes of animal extinction are due to humans, snails unfortunately included.

“You have predators coming in, such as rats in this case, which are brought by humans, and habitat loss due to humans. On these islands, which are so remote, there are no real predators for these animals, and the ecosystem is thrown off-kilter as a result. It’s a domino effect,” he said.

Slapcinsky described Easter Island as a prime example of the damage humans can do and the importance of documenting species while we still have the chance.

“After discovery, it was overpopulated very soon. The native flora was wiped out. We didn’t know there was a fauna of land snails until someone studied cave deposits, but by then things were gone. There might be things that have gone extinct that we’ll never know about. Only by documenting something can you try to save it.”

Snails aid in breaking things down by eating films off of surfaces and feeding on the detritus found in forest floors or caves. Some may even provide benefits for plants, said Slapcinsky.

Slapcinsky has done his own land snail field research in Hawaii and Papua New Guinea. He and colleagues from Hawaii were proud to discover and report the first new recent Hawaiian species of land snail described in over sixty years.

“We’ve got to do better while we still can,” he said. “We can’t afford to have things keep disappearing.”

Media Contact

Andréa Bolt

Communications Specialist

a_bolt@tamug.edu